Articles

MSM:

Why Three Letters Matter

More Than You Think.

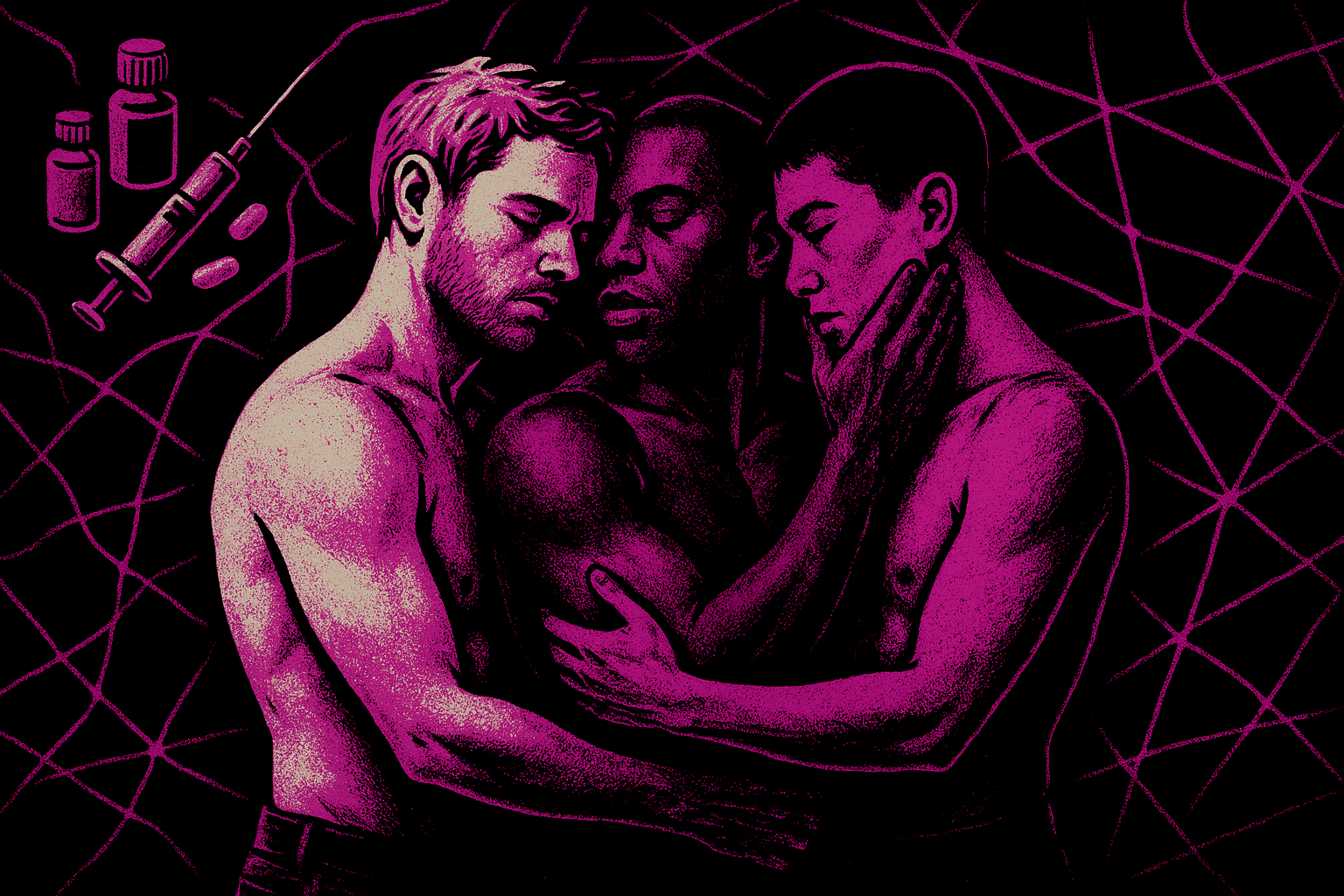

Introduction: MSM. Three Letters, Many Lives.

Men who have sex with men.

It’s not a term you hear at a party. No one introduces themselves as “an MSM.” It lives mostly in clinic notes, research papers, funding bids, and surveillance reports. It feels bureaucratic, flat, almost cold. And absolutely not part of the vocabulary of an average person to define a person.

And yet, these three letters quietly shape who is seen, who is funded, who gets counted, and who is left out.

In my work on chemsex and digital platforms, MSM isn’t just a technical acronym. It’s an umbrella that does two things at once: it reveals, and it erases. It helps public health systems see patterns of risk that identity labels like “gay” or “bisexual” can miss. But it can also strip away history, culture, and community, reducing complex queer lives to a single behaviour: sex between men.

This article is about sitting with that tension.

What does MSM really mean? Why is it still used? How does it help my research - and where does it fail the very people it tries to describe?

This page is part of my broader PhD work on chemsex, digital landscape, apps and public health.

What MSM Actually Means (And What It Doesn’t)

“Men who have sex with men” is a behavioural category.

It says nothing about identity, nothing about politics, nothing about community. It simply says: we are talking about males who have sexual contact with other males.

That includes:

Out gay men who live fully within LGBTQ+ cultures.

Bisexual men who move between different social worlds.

“Straight” or “DL” men who would never call themselves gay.

Married men whose partners have no idea they see men on the side.

Migrant men who never use Western identity labels but meet men via apps.

Men in prisons, saunas, parks, hotels, chemsex parties, Telegram / other digital groups.

Some of these men proudly identify as queer. Some never will. MSM cuts across all of that.

What MSM doesn’t mean:

It doesn’t automatically mean “gay community.”

It doesn’t mean “out,” “visible” or “politically engaged.”

It doesn’t tell you anything about how a person feels about sex with men - whether it is joyful, shameful, experimental, compulsory, transactional, or all of the above.

MSM is deliberately blunt. That bluntness is both its strength and its problem.

Why Public Health Needed MSM

To understand why MSM exists, it helps to go back to HIV.

Early in the epidemic, “gay men” were singled out as a risk group. That language captured some realities – but it missed others. As the crisis unfolded, it became clear that there were men who:

Had sex with men but didn’t identify as gay or bisexual.

Lived in countries where “gay” as an identity didn’t quite exist in the same way.

Were married to women, had children, and were deeply embedded in heterosexual social worlds – while still having sex with men in secret.

If surveillance systems only asked, “Are you gay?”, these men disappeared on paper. But they did not disappear from risk.

MSM emerged as a way of saying:

“We are tracking a pattern of behaviour that increases exposure to HIV and other STIs - regardless of how someone names themselves.”

In other words, behaviour matters for transmission, not just identity. MSM gave public health a way to see that.

The Quiet Power of an Umbrella Term

So what does MSM actually do in practice?

It makes invisible men visible.

A man can tick “heterosexual” on a form and still be counted if he reports sex with men. MSM stops everything being funnelled through identity labels alone.It lets data speak across contexts.

A health department in London, a clinic in São Paulo, and a community project in Johannesburg can all talk about “MSM” and broadly know they are discussing male-male sexual behaviour, even if local cultures and identities differ.It holds together very different stories.

MSM includes the man on PrEP who knows his viral load, his dosing schedule, his top/bottom preferences - and the man who has no language for any of that, who only knows that sometimes, in certain spaces, he ends up with men.

For my research on chemsex and digital platforms, this matters.

If I only looked for “gay men,” I’d miss the married guy who uses an app to arrange discreet chemsex sessions, deletes the chat history, and goes back to his family. I’d miss the migrant worker who never steps into a gay bar but knows exactly which emoji means “chems.” I’d miss the bisexual man who avoids LGBTQ+ spaces because of racism, but finds sex (and drugs) through apps.

MSM keeps those men within the frame.

Where MSM Starts to Hurt

But there’s a cost. MSM is not a word people claim. It’s a word applied to them and that matters.

When you are described only as “a man who has sex with men,” several things can happen:

You become a behaviour before you are a person.

Your history, relationships, culture and politics slide into the background. What stands out is what you do with your body, framed as risk.You can feel pathologised.

MSM appears mostly in sentences about “risk groups,” “burden,” “incidence,” “epidemics,” “intervention.” It rarely appears in sentences about joy, love, tenderness, or queer pleasure.You can feel ungrounded.

“Gay,” “bi,” “queer” come with communities and stories. “MSM” doesn’t. It’s a category without a culture, a label without a home.

For people already navigating stigma around sexuality, drugs, HIV, or mental health, this can feel like yet another way the system looks at them through a clinical microscope rather than listening to them as full human beings.

MSM, Identity, and the Messiness in Between

One of the most important reasons I use MSM in my work is that identity and behaviour don’t always match.

Consider:

The man who is “straight” with his friends, “curious” on apps, and “just helping out a mate” when sex happens.

The bisexual man who feels more comfortable in “straight” spaces but mainly finds intimacy with men online.

The gay man who does not disclose his sexuality at his GP because the last time he did, it went badly.

In all of these cases, relying on identity labels alone would under-estimate risk and under-deliver care.

MSM allows me to ask:

Who is having sex with men and under what conditions, with what substances, with which digital tools and regardless of how they describe themselves?

But I also have to ask:

How do these men experience those mismatches?

What does it cost to live a life where identity and behaviour diverge?

What does that do to mental health, to chemsex practices, to willingness to seek help?

MSM opens the door analytically - and then I have to walk through it carefully.

Digital Platforms: Where MSM Becomes Visible (and Sorted)

Dating apps and digital platforms don’t use MSM. They present you with a different set of labels:

Gay. Bi. Curious. DL. Discreet. No label. “Men only.” “Everyone.” “Looking for now.”

Underneath all of those options, public health would see MSM. But on the screen, what you see is a sorting system - a way of filtering, excluding, and signalling.

This is where things get interesting for chemsex.

On apps and encrypted platforms:

Some men call themselves gay and openly mention chems, pipes, party emojis.

Some men say “straight only” but appear relentlessly in spaces where other men are clearly present for sex.

Some are in couples looking for thirds; some are in no-strings binges that last 48 hours. And more.

Some use chems to feel sexually free; others use them to numb shame, trauma, or loneliness.

MSM is the umbrella over all of these digital lives. But if I stop at MSM, I miss how platforms shape and stratify these experiences:

Who is visible in the grid.

Who is filtered out.

Who is read as “safe,” “clean,” “hot,” “too much,” “too risky.”

Who is funnelled into chemsex networks quickly, and who is buffered by other norms.

The term MSM gives me the population. Digital platforms reveal the architecture in which that population lives.

Chemsex: One Umbrella, Many Storms

Under the MSM umbrella, chemsex looks very different from person to person.

Some possibilities:

A gay man who has regular, planned sessions with friends, uses harm-reduction strategies, and feels broadly in control.

A man who attends large, anonymous parties where consent blurs, time stretches, and overdose risk is high.

A married man who only uses chems during secret sessions and then tries to erase every trace, carrying enormous fear of exposure.

A migrant man who links chemsex with housing, income, or immigration precarity - sex and substances entangled with survival.

Public health often collapses these differences into “chemsex among MSM.” But those differences matter for everything: risk, resilience, intervention.

In my research, MSM is the starting point. The real work is in disaggregating:

How race, class, migration, and disability shape chemsex practices.

How different identity positions (gay, bi, straight-identified, unlabeled) interact with shame, pleasure, and help-seeking.

How digital platform design accelerates risk for some men more than others.

MSM tells me who is technically included. It doesn’t tell me how they live chemsex - or what they need from services.

Who Gets Counted - and Who Gets Lost

When public health data is reported, we often see neat categories:

“New HIV diagnoses among MSM.”

“PrEP uptake in MSM populations.”

“Drug-related harms among MSM.”

That data is crucial. But underneath it, real inequalities can hide:

White, urban, out gay men may be over-represented in clinic data and community projects.

Black and Brown MSM, migrant men, and men with unstable housing may be less likely to attend services – and therefore under-counted.

Men who identify as straight or who fear being “outed” may never disclose sex with men at all, even when they do attend.

The result is a paradox:

MSM as a category exists partly to make hidden men visible. But the way we collect data can still reproduce the visibility of those already closest to services and community infrastructures.

In my work, that means asking:

Which MSM are you not seeing in your data?

Whose chemsex experiences are missing from the narratives we tell?

How do digital tools capture some lives and erase others?

Using MSM Carefully in Research and Practice

So, why do I still use MSM in my work - and how do I try to avoid its pitfalls?

A few principles guide me:

1. Name it - and critique it.

I don’t pretend MSM is neutral. I explain what it means, why public health uses it, and what it risks erasing. I treat the term itself as part of the story, not just a background detail.

2. Combine behavioural and identity language.

I might write: “This project focuses on MSM - including gay, bisexual, queer, and straight-identified men who have sex with men.” That way, the umbrella is clear, but the diversity under it is visible.

3. Disaggregate wherever possible.

Rather than saying “MSM use chemsex,” I try to go deeper: who is more likely to use which substances, in what settings, with which digital tools, under what social pressures?

4. Stay close to lived language.

In interviews and qualitative work, I will let people name themselves. If someone never uses the term MSM, I won’t put it into their mouth. It remains my analytic term, not their identity.

5. Connect it to design, not just behaviour.

In the same way I talk about the Dopamine Loop as a collision of neurochemistry and platform design, I want to talk about MSM not just as “men doing risky things” but as people navigating risky infrastructures - clinics, platforms, laws, and stigma.

Beyond the Acronym: Toward More Caring Categories

Will MSM always be the dominant term? Maybe not. Language shifts. New frameworks will emerge. Some already are: more specific phrases like “GBMSM” (gay, bisexual and other MSM), or approaches that explicitly name race, migration, class, and gender instead of leaving them implied.

But the deeper question is this:

How do we categorise people for public health purposes without stripping away their humanity?

Because some level of categorisation is necessary. We need to know who is affected, where resources should go and which interventions work. The danger is when the category starts to stand in for the person, when “MSM” becomes a clinical shorthand that flattens queer life into statistics.

For me, the way through is not to abolish MSM overnight, but to hold it lightly:

Use it strategically, to align with surveillance data and speak to policymakers (this matters for HIV services / prevention, PrEP access and wider queer public health policy).

Refuse to let it be the final word.

Layer it with stories, voices, and digital realities that show the complexity underneath.

Conclusion: An Umbrella, Not a Cage

MSM is an awkward term. It doesn’t belong to us in the way “queer” or “gay” might. It came from public health, not from protest marches or bedroom conversations. It’s clinical, behavioural, stripped of romance.

And yet, it matters.

For my research on chemsex and digital platforms, MSM is the umbrella that ensures no one who is at risk is automatically excluded just because their identity doesn’t fit the form. It allows me to say: if you are a man and you have sex with men, you are part of the picture. Your risks, your pleasure and your struggles count.

The work, then, is to make sure the umbrella doesn’t become a cage.

That means continuously asking:

Who is under this term, and who do we still fail to see?

How do race, class, migration, disability, and digital access shape which MSM show up in our data?

How can we move from simply counting MSM to actually caring for them - in clinics, on platforms, in policies, and in the spaces where chemsex and queer intimacy unfold?

Because behind those three letters are thousands of lives. Some are loud, some are hidden. Some are in crisis, others are thriving. More so and importantly, all deserve more than a category. They deserve language, infrastructures, and futures that recognise them fully.

MSM is where the story starts. It is not where it ends.

By Clyne Hamilton-Daniels